The debate around Venezuela has turned cold. Reporters and activists live safely distant from our reality and often choose to remain there. In fact, they pretend not to know. They pretend that neutrality absolves them.

It does not.

When I speak with colleagues from the so-called first-world countries, I see a pattern: a practiced cynicism that reduces suffering to a story angle, an editorial checkbox, a headline that will not disturb the newsroom’s routine. It’s in my experience that rituals of “balance” and “both sides” become shields against the moral work of witnessing. They trade courage for career, accountability for bylines.

This is not about partisan theater or easy moralizing as if the world is black and white; it is about consequences. Silence and detachment are not passive states—they shape outcomes and they also enable harm. Silence lets abuses persist, lets perpetrators calculate with impunity, and leaves survivors with nowhere to appeal to (or to be used by) those with extreme views that have interior motives. So know that Venezuelans were and are cornered, no matter where you look from.

In the post-truth era, journalists are playing the game of politicians and choosing to be a mirror for comfortable audiences; forgetting to be a megaphone for the vulnerable and an irritant to power wherever they are in the spectrum. It’s a democratic/social contract: When you hold power to account, you also protect the norms that let reporting exist at all.

Instead of supporting journalists and outlets that take risks to document the truth, like those in Venezuela or who escaped persecution, the topic of Venezuela is used by both sides of the ideological spectrum to analyze their own political conflicts—weaponizing our struggle in ways that ignore our lived experiences, culture, and history. It’s frankly lazy journalism and performative activism.

Over the years I’ve been labeled both a fascist and a communist, and my research and expertise—based on data gathered at immense sacrifice by Venezuelan journalists and humanitarian activists—is dismissed as merely a “perspective.”

For instance, Venezuelans in the country aren’t celebrating because they still face repression and persecution under Delcy Rodríguez’s continuing mandate, not because of Maduro’s capture. I’ve seen foreign media repeatedly exposing people inside the country in ways that endanger them and destroy trust. When Venezuelans don’t behave the way outsiders expect, the media — and parts of the international left — twist that refusal into an excuse to abandon real support, instead using the story to score anti‑Trump points.

What happened in Venezuela on January 3rd is neither the worst nor the best possible outcome; conflicting emotions are valid, but clarity and accountability are non‑negotiable. Political honesty requires we remain fair even when ideology tempts us to look away from systematic human‑rights violations justified by moral abstractions.

How progressive media plays with post-truth politics

As a journalist, it’s easy to point out the media’s ethical mistakes.

Too often they operate as the mirror image of totalitarian regimes that call themselves progressive: comfortable newsrooms trade moral courage for ideological branding. Their beats align with narratives that soothe donors and audiences like the feature published by the New York Times on Delcy Rodríguez, making themselves useful to the very policies they claim to critique.

Outlets frequently focus on rhetoric and promises rather than actions, and the real manifestations of repression. For instance, news agencies like TeleSur are propaganda spreaders that people tend to quote.

Some outlets spotlight “Hands Off Venezuela” protests—organized and funded by The People’s Forum and staffed by non‑Venezuelan paid activists—to downplay and invisibilize Maduro’s atrocities while deflecting attention from ongoing repression under Delcy’s mandate. This is not balanced journalism; it’s frustrating that many outlets amplify fake voices instead of centering on Venezuelans and holding the regime accountable.

Despite posing as socialists, these governments have not delivered progressive social reforms. In fact, during this dictatorship abortion rights, LGBTQ+ protections, environmental protection to the amazons, and similar policies have not been enacted in over 25 years, but repressed even more. I would say that reporting should prioritize evidence of policy and human‑rights realities over flattering discourse. Actions speak louder than words, they say.

Indigenous communities in Venezuela are increasingly alienated: abandoned and vulnerable to guerrilla groups, and exploited by gold‑mining interests that seize land and resources, erode traditional livelihoods, and drive environmental destruction and violence. And let’s not forget to mention how indigenous voting rights were virtually abolished after the 2015 elections.

So, if you wonder why Venezuela’s victims (to the point you perceived them as “radicals”) and Venezuelan journalists distrust media, start by examining how their coverage has betrayed us, especially right now, when amid recent events, reporters have so diligently found the opportunity to revise the history of our struggle and once again minimize and oversimplify the damage made by Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro. All of that so they can oppose Donald Trump as if it can’t be done otherwise. Reporting on Venezuela needs the media to be grounded and focus on accuracy.

I’m aware of how, when we Venezuelan journalists get the chance to publish pieces exposing systematic human‑rights violations—with legal arguments and clear proof of the usurpation of the presidency in 2019 and then in 2024, as well as the politicization of public institutions—we get pushed into the opinion section, reduced to a patronizing footnote while the outlet washes its hands like Pontius Pilate.

It’s just sad this is the platform and the level of respect we have available, since the Venezuelan regime has closed over 400 media outlets; freedom of expression is effectively nonexistent, pretty much criminalized.

Calling Maduro “president” without context is misleading: it confers legitimacy on a contested and internationally unrecognized authority after stealing the presidential elections in 2024; normalizes abuses and impedes accountability; flattens complex legal and political realities into misleading “self-proclaimed” headlines; and retraumatizes victims by treating contested power as settled fact.

Venezuela is caught in a dangerous power struggle that has already undermined even further our sovereignty. Because, newsflash! Most are already late to notice that our sovereignty has been violated for YEARS. The Maduro regime has funneled national wealth to bolster foreign powers while allowing Russian and Cuban military presence for repression purposes and enabling guerrilla and terrorist groups to operate with impunity.

When it comes to oil, Venezuelans are wary of Trump. We are celebrating Maduro’s capture on the stands of human rights and justice. We know that much of our country’s wealth has already been siphoned. Iran, China, Russia, and Cuba have extracted control or profits from Venezuelan oil to bankroll their own interests and, in some cases, enable violence.

Venezuela’s oil has funded Russia’s invasion, Iran’s Hezbollah, Cuba’s autocracy, and China’s interference agenda in the Western Hemisphere.

Cuban military personnel were present and suffered the most casualties during Maduro’s capture, which is another evidence of how Venezuela’s sovereignty had already been compromised before any external intervention was publicly discussed.

Saying Venezuelans “should know” about oil geopolitics is patronizing and questions our intelligence. We already know: foreign powers and regime allies have long siphoned the country’s wealth and infrastructure. If anyone truly cared about Venezuela’s resources, they would have condemned Maduro years ago, not now as a talking point.

But let’s clear: we also know the Trump administration pursues influence over our resources under the guise of promoting democracy. Do not lecture us on things we are pretty much aware of. We also don’t need history lessons as we understand the possible scenarios but our own history and temper. Above all, we don’t need told-you-sos. It’s out of touch and deeply ignorant.

It seems the international community is more worried about being right about Trump than to let Venezuelans celebrate that justice (at least for Maduro and Flores) was served.

The oversimplification of the Venezuelan crisis

In my years studying in Europe, I was often “schooled” about my country’s collapse—as if I hadn’t watched it crumble brick by brick myself. It was humiliating to hear self‑important journalists and professors wave US sanctions like a magic word that explains everything, daringly mocking my firsthand knowledge with oversimplified takes on micro and macroeconomics. They sounded ridiculous… and worse, obstinately refused to listen or engage with real evidence and depth.

It dawned on me that most people understand economics and its link to politics when a lot of invisible parts of the engine are moving in their favour. But they don’t know how to analyse a crisis where all the pieces are spread on the floor because there are no institutional guarantees. I dare to say they would not know how to put it back together.

The collapse was driven by systematic looting and gross mismanagement that devastated ordinary Venezuelans; so reducing that tragedy to a catchy slogan is both insulting and dangerously misleading. Despite common belief, U.S. sanctions on Venezuela were not the primary cause of the economic collapse. The economy was already struggling.

Sanctions policy evolved incrementally: individual sanctions began earlier in 2005. But targeting individuals who syphon resources for personal use and commit violations of human rights, differ from sanctions aimed at the oil industry with broader sectoral measures starting in 2018–2019.

By the time major 2019 sanctions were imposed, Venezuela’s economy was already severely damaged by falling oil output and prices, chronic policy failures, hyperinflation, shortages, and capital flight. But it is true that those sanctions intensified external pressures to constrain oil revenues and transactions. I am not condoning it.

Expropriations accelerated in 2003, culminating in large‑scale seizures around 2007. The policies produced declining investor confidence, constrained access to foreign currency, and collapsed many industries, including the energy sector by 2010. Lack of property rights intimidated independent business owners and civil society—enforcement was often selective against critics of Chavismo—deepening state control over livelihoods and shrinking the space for economic pluralism.

Since 2008, Venezuela doubled down on oil‑dependent, procyclical spending amid high prices while continuing nationalizations and intervention in contracts. Investment in oil infrastructure fell (e.g. Amuay Tragedy), and efforts to diversify the economy were neglected; leaving the country more exposed to future price shocks.

A multi‑year and sharp decline began around 2012 and worsened by 2016, driven mainly by domestic mismanagement and earlier shocks. The country’s GDP fell dramatically after 2012 (about 60% by 2018 and 88% by 2020) —while our oil industry’s underinvestment, corruption, and firing of skilled staff, as early as 2002, collapsed oil production and export revenue.

Hyperinflation from 2017 wiped out incomes and confidence in the Bolívar; fiscal deficits were monetized, reserves and external financing were depleted, and public finances became unsustainable. Chronic shortages of food, medicine, and basic services, widespread malnutrition due to Maduro’s Diet, and capital flight had created a severe humanitarian crisis by 2018.

The resulting brain drain and mass migration compounded a refugee crisis in which over 7.7 million Venezuelans have left their country, making it the biggest displacement in recent Latin American history.

This is all politically linked, which in my humble opinion, started with the infamous act of the Tascón List in 2003 and the São Paulo Forum.

Chávez and Maduro bear clear responsibility for Venezuela’s collapse: through politicizing PDVSA and state firms, orchestrating widespread corruption and looting, and eroding the rule of law and property rights, their policies hollowed out the country’s productive capacity. Reliance on oil rents without diversification (making up for around 90% of our imports), combined with price controls and exchange interventions, created chronic shortages, black markets, and fiscal fragility that transformed temporary shocks into a long‑term economic rupture.

In 2014 the oil‑price crash was the perfect excuse for the government to centralize power and deploy security forces to suppress growing protests; demonstrations were met with mass arrests, lethal force in some cases, and heavy-handed crowd control. During the peak of protests in 2014, 2017, 2019 and 2024, protesters, bystanders, journalists, NGO workers, and opposition leaders faced harassment, lethal force, criminal charges, and intimidation, narrowing space for dissent and independent reporting.

Those policy choices also had profound human‑rights and political consequences: the collapse of public services (health, water, power) and the dismantling of institutional checks produced severe violations of economic and social rights, impunity for elites, and targeted repression of opponents.

Venezuela was already a welfare country

For those in the back cheering that Chavismo brought unprecedented welfare: Chavez did bring change, but it was a mirage and an active effort to erase history.

The country historically provided universal public services. Venezuela before Chávez nationalized oil in 1976 and already supported extensive social programs: publicly funded preventative healthcare, free higher education, and wide social subsidies.

Even before 1976, after the University Law was passed in 1958, my grandparents and then my parents went to university for free and never had to worry about a hospital bill.

Chávez expanded access to some of those services, but it’s infuriating to watch how that history was twisted with years of media repetition of false rhetoric. If anything, in the 1990s, Venezuela was a welfare country that needed regulation and expansion, not patronage control.

Chávez and Maduro’s politicization of institutions, rampant corruption, and reckless economic policies strained finances and hollowed out capacity, turning once‑free healthcare and tertiary education into systems now plagued by shortages, degraded quality, and de‑facto privatization that leaves ordinary people worse off.

Now, millions of Venezuelan households have been pushed below the poverty line (around 90%), with many relying on informal work, remittances, or humanitarian aid to survive.

Who is accountable?

U.S. citizens are completely right to question the means; they should use their still‑functioning public institutions to challenge the administration’s legality. Yet, the ousting of Maduro was a necessary step toward restoring accountability and protecting Venezuelans’ human rights. This should be defended even as people scrutinize how transitions are carried out.

It’s possible—and important—to hold both truths at once: the ousting of Maduro is a net positive, while U.S. citizens and global and American institutions must rigorously scrutinize the legality and methods used.

I see worrying similarities between Trump and Chávez: populists who attack the press and promote polarization, using resources to buy loyalties. Sometimes it feels like Trump is following the same playbook. My wish is for Americans to be vigilant!, and not from an ideological stance, but from a human‑rights and policy perspective.

This is never straightforward. As journalists, we want to feel enlightened, clear‑headed, and give our audience certainty. The U.S. intervention in Venezuela is not an ideal scenario: all actors and politicians involved, directly or indirectly, are unpredictable and their words are not always reliable. Trump and the Venezuelan regime, now led by Rodríguez, are both known to do the impossible to deviate, buy time, or distract people to escape/delay accountability from outside and inside their countries. That makes our job harder, but it is precisely our duty to keep them accountable.

Venezuela is a perfect pretext. The U.S. has plainly tested the waters by using the crisis to advance geopolitical interests under the guise of democracy promotion. It is also valid to say that the world has failed Venezuelans. Organizations and governments around the world, especially in Latin America were complicit and downplay 25 years of democratic deterioration into a criminal state.

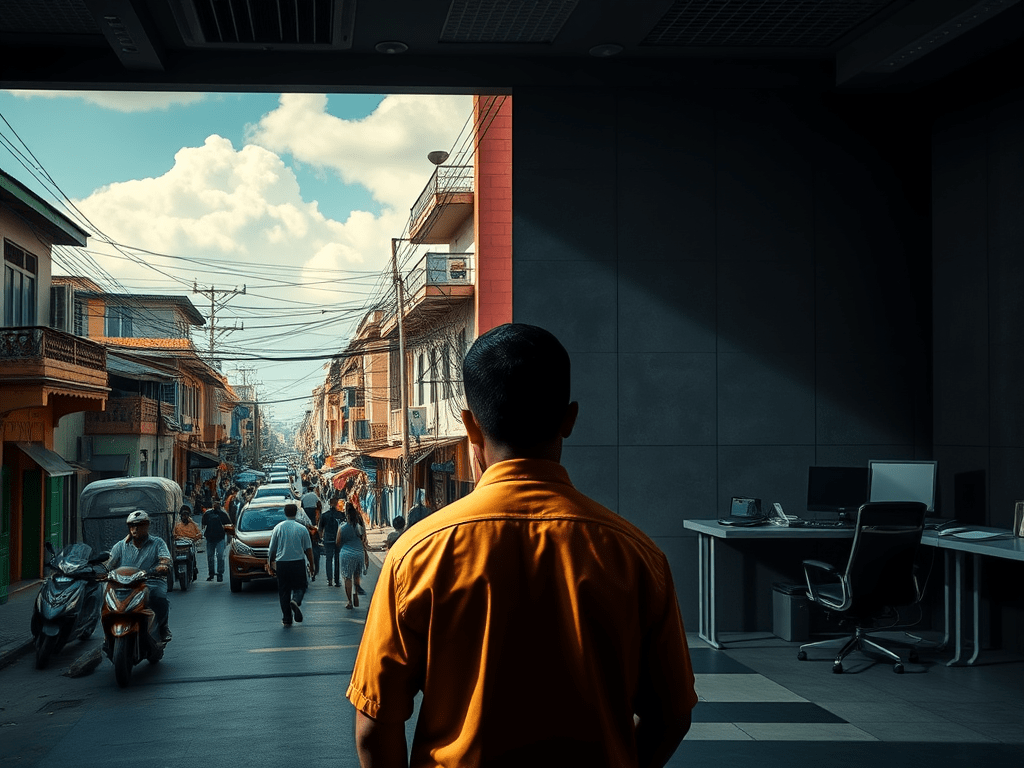

Please don’t assume we had more options before January 3rd. We are between a wall and a hard place. Venezuelans don’t have the privilege of observing this abstractly; we wish the means were different. We wish the results of the 2024 elections were respected. We wish that the 2015 coup d’état to the National Assembly didn’t happen. We wish we were not killed and disappeared every time we try to protest or for sending a message of discontent.

Comment